I modelled the carbon impact of football team travel using SAF, conventional flights and public transport. Here’s what I found.

Sustainability strategy and insight for sport

In 2015, Arsenal’s 1-1 draw with Norwich grabbed headlines, but not because the team missed the chance to go level on points with leader Manchester City. Rather, the club was slammed for taking a 14-minute flight to a match just two-and-a-half-hours from their home stadium. One of the more jaw-dropping examples of domestic flying by UK football clubs, even 10 years ago, this decision to fly was criticised as ridiculous.

Who ever said all press was good press?

Football has faced major criticism for its travel choices, particularly chartered private flights which have become a reputational issue for Premier League teams. A BBC investigation revealed that at least 81 domestic flights were taken by Premier League clubs in the space of just two months. But while Premier League teams are the main offenders, clubs across all levels of the EFL pyramid also opted to fly to matches last season.

Plane travel is objectively bad for the environment: the aviation industry accounts for approximately 2.5% of annual global emissions. Recent innovations have seen the rise of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), promising up to 80% reduction of lifecycle emissions. Could these fuels be the solution to sport’s flight controversy?

What are SAFs?

SAFs have been approved for commercial aviation since 2011 and can replace conventional jet fuel without engine modifications, blending up to 50%. Made from renewable sources like agricultural waste and used cooking oil, they can cut GHG emissions by up to 80% over their life cycle.

While both SAFs and conventional fuels emit CO2 when burned, SAFs use carbon already in circulation, absorbed by plants during photosynthesis. Some SAFs also contain fewer impurities, reducing soot, sulphur dioxide and particulate emissions.

Where does SAF fit into sports?

Given its lower lifecycle emissions, using SAF has been tipped as a straightforward way for sports organisations to reduce their carbon footprint, with a number of sports teams venturing into this space, partnering with various companies to promote its use.

Mercedes F1 was the first global sports team to invest in SAF in 2021. In the same year, Valencia CF travelled to its match against Sevilla on Air Nostrum’s first SAF flight. Last year, there was news of Formula 1 investing in SAF and Formula E and DHL partnering to transport freight from Berlin to Shanghai using SAF blend jet fuel.

And, in the US, the San Francisco 49ers became the first NFL team to purchase SAF to cover its match-related flying on United Airlines to and from LA in September 2024.

However, not all of these teams have used SAF directly on their flights. Many SAF deals involve purchasing enough SAF to cover the distance flown, where it is subsequently used on a different flight. For example, private jet provider, Victor allows customers to choose how much SAF to purchase, before relaying this to its partner, Neste (SAF provider) which releases the SAF to be used by one of its partner airlines.

A realistic solution?

The the most obvious solution for sports clubs to cut their flight emissions is to stop flying. But it’s not that straightforward; as sports become increasingly international, travel emissions are inevitable, and flying is often the most convenient and quickest mode of transport. SAF offers a simple solution to reducing these emissions.

However, it could be argued that putting SAF forward as a solution to high emissions from flying does not inspire fundamental behavioural change. For fans, teams deciding to fly to matches, instead of opting for alternative modes of transport, can represent a deprioritising of climate issues – regardless of fuel type.

Should clubs be setting an example and stop flying, instead of buying their way out of their emissions by purchasing SAF?

At university, driven by my concern for sports' environmental impact, I developed a carbon accounting model to assess fan travel emissions at Bristol City matchdays. The analysis revealed significant emission reduction opportunities, especially through public transport.

Now, I turn this same model to look at the other side of the coin: the team’s travel. While cars are typically the most popular mode of transport for fans on matchdays, you are significantly less likely to see a convoy of Bugattis and Bentleys travelling up the M62 with the likes of Mo Salah and Arne Slot riding shotgun.

Despite this, the same reasoning applies to team travel – making use of the UK’s extensive rail network or chartering a coach to away matches could significantly reduce emissions. To put this to the test, I analysed 14 one-way domestic flights taken by English football clubs in recent seasons, all of which made headlines for their environmental impact.

For the investigation, emissions were modelled based on a typical squad of 30 people, including players and key coaching staff. Emissions factors were taken from DESNZ 2024, and the best-case scenario for Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) was used, estimating that it could reduce emissions by up to 80% compared to conventional jet fuel. Flight distances were calculated from airport to airport, with no adjustments for additional travel to and from each location. These ranged from 154 km to 292 km.

For comparison, I calculated the same journeys using ground transport, this time measuring the full distance from stadium to stadium. These ranged from 209 km to 405 km.

The question was straightforward: given the emissions savings that SAF can offer, is flying still justifiable, or do alternative modes of transport present a more effective solution?

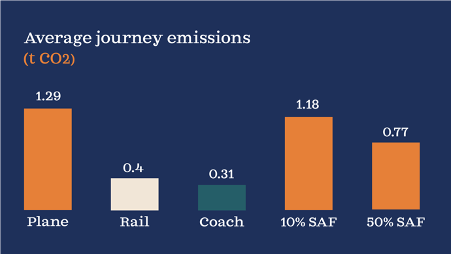

On average a single airport-to-airport flight using conventional jet fuel produces as much emissions as just over four stadium-to-stadium journeys by coach, or just over three journeys by rail (despite the longer distance).

Even with a 50% SAF blend, a single domestic flight emits more than double what a stadium-to-stadium coach journey would, and just under double that from a rail journey. With a 10% blend of SAF, those numbers rise to over 3.9 coach journeys or 2.9 rail journeys.

The difference in emissions between coach and rail, versus plane is stark: even with a 50% blend of SAF, flying emits far more than choosing to take an alternative mode of transport. Now just consider how drastic the difference could be for electric, hybrid or alternatively-powered coaches.

Switching to SAF can lower emissions, but the impact varies. A 50% SAF blend reduces lifecycle emissions by ~40%, while a 10% blend offers only an ~8% reduction compared to conventional jet fuel.

With the UK government currently mandating just a 2% SAF blend in all flights departing the UK, the potential for significant emissions cuts feels limited. At the same time, countries like France are taking more drastic steps by banning domestic flights that could be replaced by train travel within two-and-a-half hours.

Ultimately, while SAF offers some emissions savings, the data makes one thing clear – reducing football’s climate impact isn’t just about fuel; it’s about rethinking how teams travel in the first place.

SAFs aren’t the only solution, but they are part of it

The defence for flying often revolves around tight schedules, player rest, and the perceived time-saving benefits. However, there is limited evidence linking air travel to improved player performance.

Beyond the emissions from flights themselves, there are hidden impacts that aren't always accounted for, such as ghost flights - empty planes flown to reposition for the next leg of their journey - and the formation of contrails, which have been shown to have harmful effects on the environment. These factors add another layer to the argument, suggesting that flying is far from the most sustainable option for sports teams.

One major criticism of SAFs is that some are produced using crops or land that could otherwise be used for food production. As the name suggests, “sustainable” aviation fuels are designed to be a sustainable alternative to conventional jet fuel, not to take away land from food crops. The aim is to find a way to meet aviation's fuel needs without compromising food security or environmental resources.

Of course, for international flights where train and coach aren’t viable alternatives, SAFs are a great innovation that can cut aviation emissions significantly. However, certainly for domestic flights, it seems there must be a better solution than making a small fuel substitution.

What does the future hold?

Will we see more SAF partnerships popping up in the world of sports? Will teams cut out their domestic flights, and join the 14 clubs already signed up to the sustainable travel charter? Will the UK government take their SAF mandate further, or introduce a ban on domestic flights as France has done?

Great article and analysis. I will link to it in next week's Sustainable Motorsport Roundup.

This was a great read. I enjoyed the critical analysis of sustainable aviation fuel. It's also good you pointed out the argument of domestic flights contributing to player rest.

This was an angle I was looking at. However, the time it takes to commute to the airport, pass airport checks, and also commute to the stadium may defeat the purpose of speed and convenience.

Anyway, I am keenly interested in the carbon management and climate reporting sides of sports. It would be great to connect with you and learn more about your work.